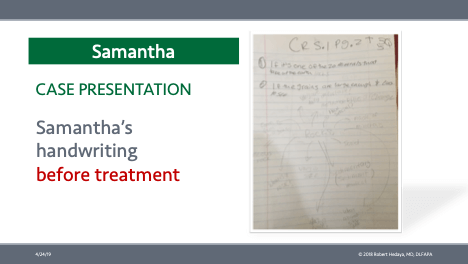

Samantha, a 14-year old girl, was brought to my office by her mother. When I first saw her, she was withdrawn, barely made eye contact, and had her headphones in even as she was answering my questions. She was depressed, had been diagnosed with ADD, and an anxiety disorder, but her mother did not want to put her on medication, so she sought my help. Importantly, Samantha was having episodes of crying, rage, and extreme irritability seemingly randomly, and they could occur anywhere and anytime. Feeling terrible remorse, and extreme embarrassment, her self-esteem, and social life suffered greatly.

A careful history convinced me that her attention deficit was due to the under-function of her prefrontal cortex (the thinking brain, behind the forehead) and excessive activity in her emotional brain, specifically the amygdala. Specifically, it seemed that most outbursts occurred after she ate junk (high simple carbohydrates, like cookies, soda, fruit, candy) food (which was lots of the time).

So, at the time of my evaluation, my hypothesis was that her inattention and anxiety were generated by her inability to think due to her poor diet. I directed her mother to clean up her diet and start using caprylic acid, which would provide a steady stream of non-glucose/sugar-based energy to her brain. It helped remarkably.

Her outbursts were caused by an overactivity of the amygdala, due to an under activity of the thinking brain. The amygdala determines whether things happening in the environment are worthy of concern (salience) and whether the appropriate response is fear, aggression, or interest (sex). The amygdala makes these determinations before there is any conscious awareness or assessment of an event. (The salience of a situation is determined based on past experiences with similar situations and cues, and it is linked automatically to a response: fear, rage/anger, or sexual interest. When the amygdala is activated, the thinking brain is largely turned off. When the thinking brain is activated, the amygdala is more quiescent.)

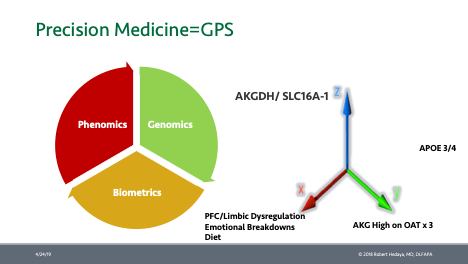

After various tests, we determined that Samantha had a genetic weakness. She had several poorly functioning copies of a gene that made too little of the enzyme called alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (AKGDH). Supporting this, was the fact that her levels of alpha-ketoglutarate (AKG) were high on three tests. AKGDH is primarily responsible for taking sugar from foods, and turning it into the energy molecule ATP, needed to keep the nerve cells working.

Importantly, these specific AKGDH genes are only present in the prefrontal cortex (i.e. other AKGDH genes do that work in other parts of the brain). To make matters worse, the low amounts of enzyme made by the gene would become less effective at their job of making energy for the thinking brain, if blood sugar levels went too high.

That explained why her outbursts were related to food. Most of the time, Samantha was working with a prefrontal cortex that was half asleep for lack of energy. How could she possibly pay attention? And anxiety would be sure to follow, for how could she possibly keep up with the growing academic demand? And most certainly, depression and low self-esteem would have to follow. Fortunately, she was not inclined to substance abuse to alleviate her pain!

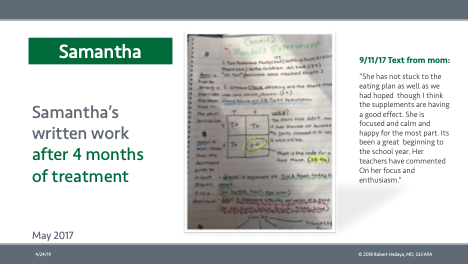

Fast forward 18 months: Samantha is in a new more academically rigorous school (she was barely getting by before), staring in local and in-school media, happy, thriving, and medication-free.

This case illustrates the benefits of precision medicine as applied to the careful history, detective work, lab work, and lifestyle changes which result in meaningful and long-lasting change.